As we near the end of the 2019 hurricane season, we look back on Hurricane Barry. As the first hurricane of the season, Hurricane Barry, was a relatively small storm and not nearly as impactful as some that came later. However, understanding it can give us a better understanding of the short-term and long-term impacts of severe weather. There are changes that can be made to help minimize the impact of severe storms both small and large, and we will discuss some of those options in this article.

Hurricane Barry made landfall as a Category 1 hurricane near Intracoastal City, Louisiana and quickly weakened to a tropical storm. Although Hurricane Barry didn’t pack the tremendous power of a Category 5 hurricane like Hurricane Katrina, it was still dangerous and life-threatening. Over 20 inches of rainfall was predicted to inundate the New Orleans area before the hurricane moved north to Baton Rouge and east to Biloxi, Mississippi.

Louisiana Gov. John Bell Edwards did not issue a mandatory evacuation order, but he did warn that residents needed to prepare for potential life-threatening flash flooding. “Every storm is different,” Edwards said. “My concern is we have a lot of people going to bed tonight thinking the worst is behind them, and that’s not the case.”

Barry was poised to challenge the environment of the Gulf coat and lower Mississippi Valley. The region faced a rare combination of issues including the storm’s anticipated tidal surge, the torrential downpour, and the record-high water levels in the Mississippi River. During Hurricane Barry, the Mighty Mississippi was at flood stage with nowhere to go but over the banks and levees. The potential to send storm surge upriver and overtop levees could have inundated New Orleans and shut down global commerce.

Hurricane Katrina’s storm surge increased the water level in the river by 13 feet, but the river was low. During Barry, the Mississippi was within 2 feet of going over its manmade levees. The situation was potentially very dangerous.

Coastal ecologists with the Water Institute of the Gulf in Baton Rouge were worried about how the eco-system would respond to this tropical storm. Louisiana’s coastal marshes are under attack because of on-going development, climate changes in the Gulf area, and continual flood-control measures. These flood control measures prevent natural coastal shoreline replenishment and impact the habitat of coastal wildlife.

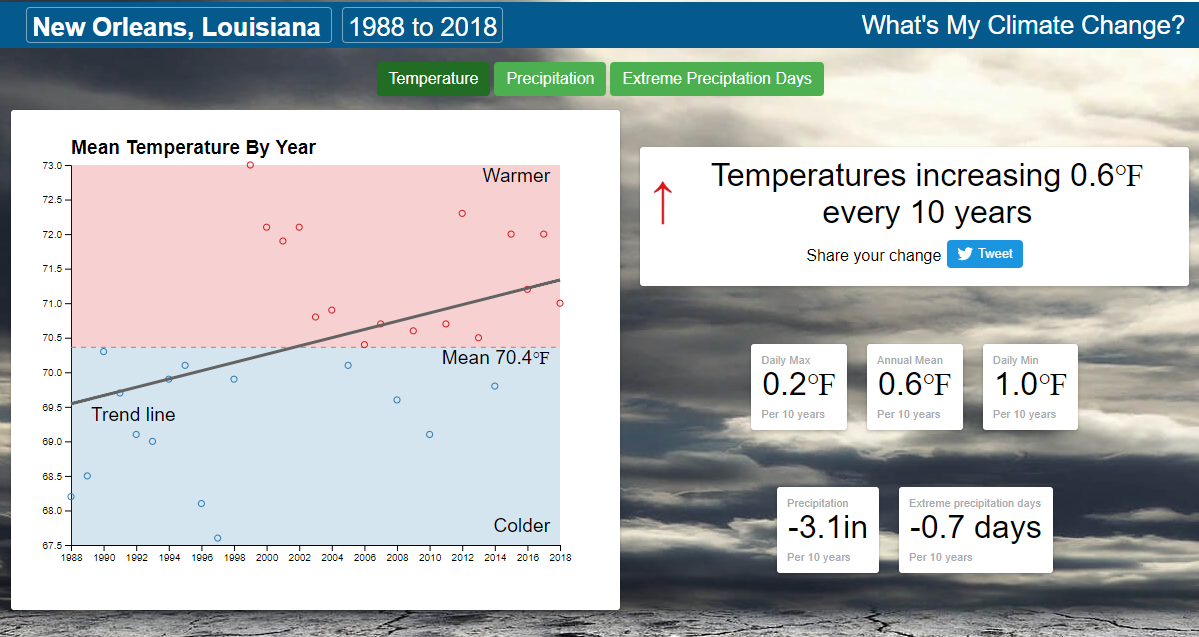

There will be definite short-term effects on the ecosystem, but what the problem illustrates: a longer-term trend of heavy rainfall due to climate change that could change the habitats of Louisiana’s fragile wildlife and change the ecosystem of the Mississippi. Climate reports state that the temperature in New Orleans from 1988 to 2018 increased by 0.6°F every 10 years. Temperature increases could worsen the spread of tropical diseases and lead to more frequent flooding rainfall events.

Coastal Louisiana floods in at least three ways. For the first time in recorded history Hurrican Barry included all three threats at one time. Floods occur in coastal Louisiana from water flowing down the Mississippi, rising seas from the Gulf of Mexico, and storm surge, and from rainfall steadily increasing in intensity due to climate change.

Are there any solutions?

Scientists have identified methods to reduce the flooding dangers to the New Orleans area and other Gulf of Mexico coastal areas. One way is to reduce runoff into the river by increasing the capacity of communities and farms along the Mississippi to slow water and retain water before it reaches the river. Reducing runoff into the river can be done by catching water where it falls, increasing soil permeability and water filtration, and developing porous surfaces and catch basins.

A second option is to use river sediment and nutrients to build up wetlands. Over 100 years ago, the lower Mississippi River System kept the river’s sediments out of its wetlands. The levees keeping the river out of homes are damaging the ecosystem of the river.

The plan under consideration is to capture 1000 million tons of sediment that flows past Louisiana annually and develop restoration projects called sediment diversions. These sediment diversions will be constructed into the levees of both sides of the river south of New Orleans. Sediment will be delivered to wetlands which will eventually build and sustain tens of thousands of acres of land.

The best solution for Louisiana and the world is to think differently about how to meet the challenges of climate change and the future. It is impossible to control the river, but Mississippi River management must face the challenges of balancing navigation or river traffic, flood protection or levee building, and restoration must be instigated to combat changes in climate and landscape. Congress needs to fund long-studied solutions throughout the Mississippi River basin in Louisiana before the next hurricane. A level 5 hurricane, plus the Mississippi at the present levels, and damaged ecosystems will be devastating for New Orleans and the rest of the coastal Mississippi areas.